In the interest of full disclosure: on 8 November, Election Day in the United States, I wrote a short piece intended to be part of the roundup of responses to the elections by Jadaliyya co-editors (if you have not read this excellent set of reflections yet, they can be found here). I sent off my neat thousand words around 7:30 on the night of the elections, and then settled in to watch the results. A few hours later, I wrote a slightly worried but not yet definitive email to my fellow editors: “ps if Trump wins tonight please kill this piece. I don`t think it will still make sense. Hopefully that won`t be necessary...”

By the early hours of the morning, things had become more clear, necessitating one final panicked email: “Looking more like Trump by the minute. Who would have fucking thought it. As I say, please kill the piece if so—I`ll write something else eventually, but this would look silly in that case.”

This is a roundabout way of saying that, as it did for so many others, Donald Trump’s victory in the US Electoral College (as of this writing, he trails Hillary Clinton in the popular vote by more than two million votes) came as a complete surprise to me. The fact that so many respected colleagues and commentators on the left were equally stunned by the results offers cold comfort.

One small part of the analysis necessary in the wake of Trump’s victory has to do with dissecting what led so many of us to underestimate his chances of winning. There are of course many elements to this, but I would suggest that one important part of this collective error had to do with not sufficiently believing our own analyses regarding the fatal weakness of Clinton as a candidate who combined the worst elements of neoliberal economic policy with the worst elements of hawkish neoconservative foreign policy, held together by a cynical co-optation of feminism and multiculturalism. Given that one of the revelations of the primary season was that a significant proportion of the US voting population (and an even more significant percentage of young voters) currently support positions that are recognizable as democratic socialism, this is not a mistake we can afford to make again.

I also agree with my colleague Ziad Abu-Rish that another important cause of the shock that greeted Trump’s victory has to do with the lingering effect of US exceptionalism, including among those of us on the left. As he puts it:

“Donald Trump is the next US president because a plurality of those that voted in the recent elections preferred him over Hillary Rodham Clinton. His victory is not the result of some deviation from an American value or destiny. It is the product of both structural and contingent factors that those who are shocked were blind to, and most of us are complicit in.”

If indeed Trump’s victory heralds “the death of US exceptionalism,” as Abu-Rish suggests, then this is itself a reason for cautious optimism.

Indeed, as I will suggest below, there are a number of avenues for optimism in the wake of the election—or, at the very least, reasons to stave off despair. I say this with some caution, and indeed, the primary reason for not publishing what I wrote before the election was that it seemed absurd, bordering on obscene, to strike an overtly optimistic note immediately following Trump’s victory. It’s not that I don’t agree with my fellow co-editor Noura Erakat that no matter the results of the election, we would have had to deal with the dangerous empowering of white supremacy, or with my colleague Mouin Rabbani that a Clinton administration would have been disastrous for the region. But given the very real fear unleashed by Trump’s victory, especially among members of those many communities who were threatened and dehumanized by Trump and many of his supporters and have been the victims of hate crimes since the election—together with the need to express the unshakeable conviction that Trump’s horrific policies will never be accepted or normalized, expressed in the immediate and ongoing protests and unrest following the election—a first response that was primarily optimistic would have been incomplete, to say the least. Another way to say it is that, in the hours before the election, I believed that what we were facing was a very poor best-case scenario; instead, we face a worst-case scenario which we must admit (all arguments about lesser-evilism aside) is very much worse indeed.

And yet, re-reading the short piece below (which, in the spirit of honesty, I publish in its original form, with some additions following it), I believe that the causes for hope that existed before Trump’s victory still exist, particularly those related to youth-led movements for significant structural change in US politics. This may be a moment for sober and clear assessment, but it is not a moment for despair. Indeed, Antonio Gramsci’s old chestnut about the need for optimism of the will to accompany our pessimism of the intellect never seemed more apt. If this has become something of a cliché, it may be because it is seldom accompanied by Gramsci’s further insistence that “The starting-point of critical elaboration is the consciousness of what one really is, and is ‘knowing thyself’ as a product of the historical processes to date, which has deposited in you an infinity of traces, without leaving an inventory.” “Therefore, he concludes, “it is imperative at the outset to compile such an inventory.”

In attempting to fulfill the demands of such an inventory, what follows is, first, what I originally wrote on 8 November, in the hours before the election, followed by a few notes on internationalism written twenty days into the era of President-elect Trump.

*

Vote for Internationalism—Starting on 9 November

Amidst the muck of the actual election, happening as I write this, let me pull out, implausible as it may seem, a moment of hope from the campaign leading up to it, and a moment of possibility now that it is, finally, over.

Arguably the biggest surprise of the primary season—even more than Donald Trump’s ostensibly unforeseen rise to power, which in retrospect can be seen more clearly as the GOP’s decades-long flirtation with white supremacy, xenophobia, and fascist-style populism come home to roost—was the fact that an avowed socialist came within shouting distance of capturing the Democratic Party’s nomination. This despite the fact that, as we now know thanks to leaked emails, the party’s leadership did everything possible to stymie Bernie Sanders’ campaign. As a result, as Ajay Chaudhary has recently pointed out, we have discovered from polls that roughly fifteen to twenty percent of Americans identify, in essence, as democratic socialists (he hastens to note that this good news needs to be balanced by the discovery, in the same campaign, that another fifteen to twenty percent of Americans are “straight-up Nazis”). This number is significantly higher among young Americans, the majority of whom, according to a recent Harvard University survey, reject capitalism and a third of whom identify as socialists.

The energy of young supporters was arguably the most exciting aspect of the Sanders campaign, which brought, for an extended moment, a sense of possibility and exhilaration to the scripted world of American electoral politics. But outside of electoral politics, this energy can be seen even more clearly in movements that have come to change the political landscape: youth groups working in the area of immigration rights, such as the Immigrant Youth Justice League and United We Dream; groups such as Strike Debt that have come out of the Occupy movements; the many youth groups that have joined the struggle around indigenous rights, being fought for most conspicuously and most bravely today at Standing Rock; and, perhaps most impressive of all, Black Lives Matter, a movement that has fought its way to the center of the American political consciousness—and has, along the way, forced into visibility the most hideous manifestations of white supremacy that continue to underwrite US society, which the Trump campaign has been all too happy to try to harness.

But the one important aspect missing from the Sanders campaign, and the one strand perhaps most necessary for any emergent left to bring into existence in the aftermath of this election, is a radical vision of internationalism. This absence has continued, depressingly, into the general election campaign. Following the US public’s large-scale forgetting of the illegal invasion and occupation of Iraq—for which no US political or military leader has ever had to face consequences—internationalism in the general election campaign could be reduced to repeated refrains of “ISIS ISIS ISIS,” and the “global role” of the US debated as a choice between benevolent protector of refugees (created, of course, as a direct result of the chaos unleashed by the Iraq war) or paid mercenary state. Somehow, American innocence has survived in the political sphere, despite the fact that the US is now currently at war in five countries, and almost solely responsible for setting in motion the greatest crisis of migration in the history of the world.

In this context, the fight to make a radical internationalism part of any emergent left in the US has never been more crucial. The best case scenario for this election by the time this piece is published is that the US will have a President and Senate Majority Leader (Charles Schumer) who both voted to authorize the Iraq war, who hold to the most hawkish positions on Israel-Palestine imaginable, and who have been among the strongest sabre-rattlers towards Iran—going so far, in the case of Schumer, as voting against the nuclear deal with Iran. Clinton’s embrace of the august war criminal Henry Kissinger has been well documented, but more disturbing has been the willing support offered by the neocons who were the architects and perpetrators of the Iraq war—Paul Wolfowitz, Colin Powell, and even, if rumors are to be believed, George W. Bush himself. Whatever the electoral necessity of stopping Trumpism, the work to be done after the election is considerable, to say the least.

An emergent left, fueled by youth movements that have been stripped of their illusions about the promises of neoliberal capitalism and globalization, urgently needs to add a renewed and radicalized internationalist vision to its agenda. Here again, the youth may be beginning to show the way. A Vision for Black Lives, the platform produced by The Movement for Black Lives, is exemplary in its insistence upon linking the domestic depredations of police violence, the prison industrial complex, and systematic racism to US imperialism abroad. Most famously, this has taken the form of an unstinting support for the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) Movement, a stance that has occasioned much hand-wringing and head-shaking among liberal supporters, as well as the withdrawal of support from some previously sympathetic liberal groups. Against the common coalition-building strategy that begins from the least common denominator, The Movement for Black Lives shows the way by beginning from the necessary. It is a stance best articulated in a statement from the Dream Defenders, one of the more than fifty organizations that have joined together to launch the platform:

“As Black people fighting for our freedom, we are not thugs and our Palestinian brothers and sisters are not terrorists. For the children who are met with tear gas and rubber bullets as they walk home from school, for the families of those we have lost to police violence, for the communities devastated by economic violence and apartheid walls, we fight. To all those who believe in a world in which all people are free, join us. For those who no longer stand with Black people because of this belief, goodbye. We do not need nor want you in our movement.”

If an emergent left, led by these and other youth movements, were to truly begin from such internationalist principles, then perhaps the days ahead may not turn out to be as dire as this horrible election would lead us to believe.

*

Internationalism after Trumpism

I will simply add two additional notes on internationalism after the victory—for the time being, at least—of Trumpism. The first is to stress that in the wake of the election, one more urgent need for the left in the US is to learn from anti-fascist struggles now happening globally. This is to say that Trump’s victory needs to be analyzed, addressed, and resisted not just through a close look at what has happened in the Rust Belt, but also in the context of similar sorts of fascist and far-right electoral victories in India, Turkey, Israel, Hungary, and the Philippines, along with the potential rise to power of right-wing white supremacist parties in the UK, France, Austria, the Netherlands, and elsewhere in Europe.

Generally speaking, when the question of left internationalism comes up in the US, the reference is almost solely to Europe, most often involving the precedents of Podemos in Spain or Syriza in Greece or the gains won by Jeremy Corbin in the UK Labour Party. These are of course real and important precedents. But it is time for an expanded scope: How has the left found ways to resist in Erdogan’s Turkey, or Modi’s India, or Sisi’s Egypt? What lessons can be learned from the massive student movements in South Africa and, not far back, in Chile? What is the shape of the emerging left in Eastern Europe and Russia? What sorts of youth movements are emerging in Palestine, in Lebanon, in Morocco?

In the past, these questions would most likely have occurred to leftists in the US under the guise of the question of solidarity: How can “we,” from our privileged position, help “them”? This question (hopefully a more nuanced version of it) remains, but it is joined by the more urgent and more immediate task of finding openings to speak to and learn from ongoing movements against authoritarianism throughout the world. For this sort of work, Masha Gessen’s “Autocracy: Rules for Survival” seems like a necessary starting point.

Another necessary starting point, albeit with a very different emphasis, is Robin D. G. Kelley’s stirring call to action in “Trump Says Go Back We Say Fight Back.” Kelley provides a list of five things that need to be done right now; I agree with all of them, but will here highlight the first item on Kelley’s list: building up the sanctuary movement in the US. We might describe this as the work of developing an internal internationalism. The precedent that Kelley cites is the US sanctuary movement of the 1980s, when nearly a million refugees fled from US-backed dictatorships (not to mention US-funded wars) in Central America, prompting the founding of sanctuary cities throughout the US and efforts to provide concrete sanctuary offered by religious groups and other citizen organizations in the US. While the decimation caused by the US in Central America during that time continues today, the political coalitions and connections created by the sanctuary movement in the 1980s also continue to function today—in part to help resist the mass deportations set in motion by the Obama administration.

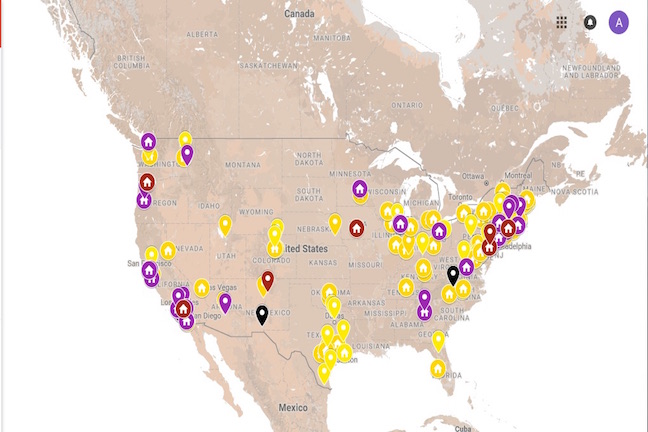

Given Trump’s promise to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program and the Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA), both put in place by President Obama’s executive orders, a new sanctuary movement today represents the most important first line of defense for the struggles to come. The establishment of sanctuary cities is one large part of this larger effort. For those of us working in the US academy, some of the most crucial work of the moment involves turning our campuses into sanctuaries, as concretely as possible. As Kelley notes, the University of California system has been among those at the forefront of this movement, recently announcing that it would refuse to assist federal immigration agents, turn over confidential records without court orders, or supply information for any national registry based on race, national origin or religion. My home campus has launched a sanctuary campaign, and there is also a City University of New York-wide sanctuary campaign, joining hundreds of colleges and universities throughout the US involved in the sanctuary campus movement). At the political level, increasing the number of sites which openly announce our non-cooperation with draconian deportation policies might have the effect of changing the political calculations of a new Trump administration, which needs to figure out which of its far-fetched campaign promises it might actually have to try to keep.

But the internationalism of a new sanctuary movement must not end there. Such a movement also hold the potential to contribute to the internationalizing of resistance politics in the US. Refugees from Syria, from Iraq, from Yemen—not to mention refugees fleeing political repression and violence in Mexico and Central America—are not simply victims of large historical forces who need to be assisted. They certainly are that, but they are also people who have had concrete political experiences and previously unimagined forms of political consciousness from which we must learn. We will need all the tools we can get our hands on for the struggles ahead. And to name our collective work as the global struggle against fascism is, unfortunately, not hyperbole, but a sober assessment of what lies ahead.

[Map of US campuses with sanctuary movements. For an interactive version of this map, click here. Image via Google Maps.]